A horrifying discovery at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Kukpi7 Rosanne Casimir says the band has found the remains of 215 children buried at the site. She notes there was always an inkling that the remains were there, but it was only confirmed this past weekend with the help of a ground-penetrating radar specialist.

“We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify. To our knowledge, these missing children are undocumented deaths,” Casimir said. “Some were as young as three years old. We sought out a way to confirm that knowing out of deepest respect and love for those lost children and their families, understanding that Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc is the final resting place of these children.”

The archivist at the Secwépemc Museum is working with the Royal BC Museum to see if there are any records of these deaths.

Preliminary work to identify the site and to see if there were any remains began in the early 2000s. The band says the work was led by its Language and Cultural Department alongside ceremonial Knowledge Keepers to ensure that it followed all of the cultural protocols given the “serious nature of the investigation.”

“With access to the latest technology, the true accounting of the missing students will hopefully bring some peace and closure to those lives lost and their home communities,” Casimir added, noting Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc is also in contact with the BC Coroners Service.

Casimir says band officials informed members of the community as well as those in surrounding communities who had children that attended the Kamloops Indian Residential School about the developing situation first. That process is still ongoing with many community members still grappling with the effects of the residential school system.

“This is the beginning but, given the nature of this news, we felt it important to share immediately,” Casimir added. “At this time, we have more questions than answers.”

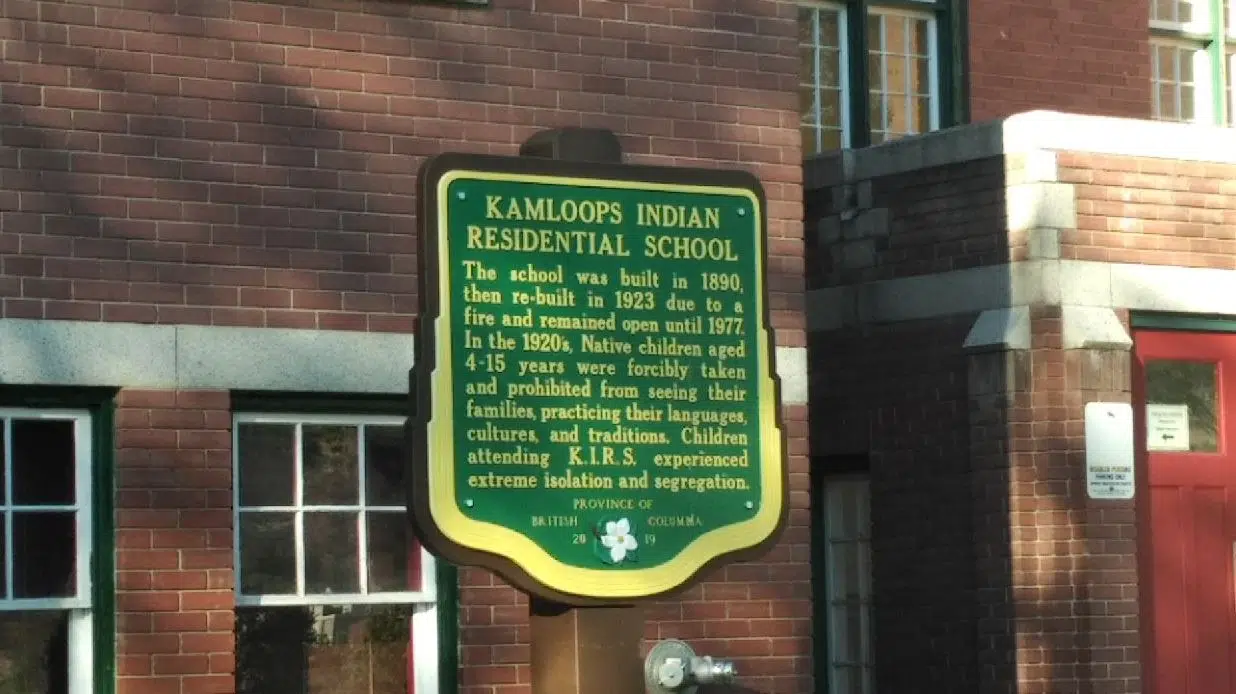

The Kamloops Indian Residential School opened on May 19, 1890, and it had its peak enrolment of 500 students in the early 1950s. The federal government took over administration of the school from the Catholic Church in 1969 using the building to house students who attended other schools in Kamloops, until it was closed on July 31, 1978.

Back in 1910, the principal said that the government did not provide enough money to properly feed the students, while in 1924, a portion of the school rebuilt after it was destroyed by a fire.

“We are thankful for the Pathway to Healing grant we received to undertake this important work,” Casimir said. “Given the size of the school, we understand that this confirmed loss affects First Nations communities across British Columbia and beyond. We wish to ensure that our community members, as well as all home communities for the children who attended are duly informed.”

As a result of the discovery, the Tk’emlups Heritage Park is closed to the public as work continues in the area with crews unsure if they will find any more remains. It is anticipated that preliminary findings will be completed by mid-June.

“This is truly heartbreaking [and its a] graphic reminder of the deplorable treatment these children and their families endured for decades,” Kamloops-North Thompson MLA Peter Milobar said.

“It’s just shocking to hear on that scale and to think that’s 215 children that families never saw them again, and then have the indignity of not even having a proper burial site or a marking at it. It’s just a really sad chapter in our overall history.”

Moving forward, Milobar says its important that Tk’emlups chief and council be supported when it comes to investigating the discovery further and trying to identify some of the people found at the site.

“It will undoubtedly open up a lot of traumatic memories for a lot of families and that’s totally understandable,” he told NL News.

“You just think of how close it is to the city of Kamloops itself, its not some rural, remote out of sight, out of mind location, and you just think of the trauma its created for generations.”

Added Anna Thomas, the president of the BC Native Woman’s Association, “I don’t have much to say at the moment about this horrific news other than I am deeply saddened. Innocent Indigenous children that never made it home to their families and communities.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) noted that large numbers of Indigenous children who were sent to residential schools never returned to their home communities. Some ran away while others died at the schools.

Students who did not return have come to be known as the Missing Children. The Missing Children Project documents the deaths and the burial places of children who died while attending the schools. To date, more than 4,100 children who died while attending a residential school have been identified.

Home communities of students:

Neskainlith, North Thompson, Kamloops, Pavilion, Penticton, Adam’s Lake, Bonaparte, Fountain, Douglas L., Okanagan, Quilchena, Shulus, Little Shuswap, Coldwater, L. Nicola, Bridge R. Enderby, Deadman’s Cr., Hope, Leon’s C., Cayoose, Salmon R., Canoe C., Lillooet, Mount Currie (Lilwat Nation), D’Arcy (Nquatqua), Seabird Island, Skwah, Kamloops, Union Bar, Head of L., Deroche, Spuzzum, Shalalth, Spalumcheen.

Tk’emlúps said it is its understanding that there were children that came from other communities not listed here.